“Gilded Rose” refactoring kata in Ruby — as if it is 2024

A “stories-first” approach to refactor a small yet complicated piece of business code

Recently, I didn’t have time or resource for serious writing. I had plans for several long articles for the summer that gone, but unfortunately not many have came of that. But last night I have stumbled upon famous (so it seems, though I have never seen it before) refactoring kata, and had an impulse for trying my hands on that, writing down some thoughts on my ways of writing code along the way.

The kata

“Gilded Rose” is a famous refactoring kata that is available in many languages. It goes like this:

First an introduction to our system:

- All

itemshave aSellInvalue which denotes the number of days we have to sell theitems- All

itemshave aQualityvalue which denotes how valuable the item is- At the end of each day our system lowers both values for every item

Pretty simple, right? Well this is where it gets interesting:

- Once the sell by date has passed,

Qualitydegrades twice as fast- The

Qualityof an item is never negative- “Aged Brie” actually increases in

Qualitythe older it gets- The

Qualityof an item is never more than50- “Sulfuras”, being a legendary item, never has to be sold or decreases in

Quality- “Backstage passes”, like aged brie, increases in

Qualityas itsSellInvalue approaches;

Qualityincreases by2when there are10days or less and by3when there are5days or less butQualitydrops to0after the concertWe have recently signed a supplier of conjured items. This requires an update to our system:

- “Conjured” items degrade in

Qualitytwice as fast as normal itemsFeel free to make any changes to the

UpdateQualitymethod and add any new code as long as everything still works correctly. However, do not alter theItemclass.

The initial Ruby implementation provided by the kata maintainer is some scary 45-line method, all made of ifs with many levels of nesting; it is a direct translation of the initial C# implementation. The suggested exercise is to refactor it in any way one sees suitable.

Several Ruby solutions to the kata can be found throughout the internet. Mostly, they take on the usual path of having a class per every item kind and frequently divide all the logic into five-word-name, one-line-body methods for each action in every class: that’s a style significant part of the community prefers lately.

My approaches to writing in Ruby are somewhat different, and I thought that I might just show how I’d solve a task like that.

“But isn’t it just a useless toy task?” No parallelism, no SQL tinkering, no sub-microsecond benchmarking… In all honesty, surprising amounts of business code written in many modern codebases are solving simple yet convoluted tasks like that; and too frequently poor expression of thoughts on this “negligible” level is what really affects velocity, stability and the design of the whole system. That’s why I am frequently talking about “phrase-level” expressiveness and method-size solutions, being principal developer and all.

Adding unit tests

The code has “integrational” tests: a script that prints the 30-day output for some items and an expected output file (which the original kata suggested to check via the specialized tool, but in a scripting language, it is easy to make the checking script from scratch).

It lacks more atomic tests, though, and that’s what we start with.

My approach to tests is simple:

- I like TDD/BDD (in the loose understanding of “write the tests before changing the code”);

- I treat my tests the way I treat my code: I want them to be easy to write and read, leveraging my language’s expressiveness to have the code as close to “clearly express the intention, and nothing else” as possible.

The latter is a surprisingly contrarian opinion in the latter years, at least in the Ruby community. I dedicated quite an emotional article article to the matter once, and I wouldn’t repeat my arguments here. I’ll just say that in my experience and experience of my colleagues, these approaches work, and I am not planning to change them anytime soon.

So, on the “clearly expresses the intention” topic. What I’d “theoretically” want to write in tests for this algorithm is something to the meaning:

- for an item like this:

- in N days, we should have these values

- in M days, we should have those values

- for another item:

- in N days, we should…

- …and so on.

That’s how I am doing it:

require_relative 'gilded_rose'

require 'moarspec'

RSpec.describe GildedRose do

before { days.times { gilded_rose.update_quality } }

let(:gilded_rose) { GildedRose.new([item]) }

alias_matcher :become, :have_attributes

describe 'standard item' do

subject(:item) { Item.new(name="+5 Dexterity Vest", sell_in=10, quality=20) }

it_with(days: 1) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 9, quality: 19) }

it_with(days: 10) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 0, quality: 10) }

it_with(days: 11) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: -1, quality: 8) }

it_with(days: 15) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: -5, quality: 0) }

end

describe 'aged brie' do

subject(:item) { Item.new(name="Aged Brie", sell_in=2, quality=0) }

it_with(days: 1) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 1, quality: 1) }

it_with(days: 5) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: -3, quality: 8) }

end

# ...and so on

This code uses moarspec, my RSpec extensions library (which tries to be ideologically compatible with RSpec, just taking its ideas further), namely its recently added it_with method.

This method is just a shortcut for what RSpec already has. This code:

it_with(days: 1) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 9, quality: 19) }

..corresponds to this vanilla RSpec code:

context 'when it is day 1' do

let(:days) { 1 }

it { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 9, quality: 19) }

end

…and is indispensable when you need to write a lot of tests for the same piece of logic, specifying the correspondence of various parameters to expected values.

The rest, like implicit testing of the subject (it { is_expected.to implicitly applied to what is declared as a subject above), and expressive matcher is what RSpec already provides. Though again, using many of these tools isn’t that fashionable lately.

This is not the only way to make a concise test for input/output pairs. Other options are truth tables, something along the lines of:

{

1 => {sell_in: 9, quality: 19},

10=> {sell_in: 0, quality: 10},

11=> {sell_in: -1, quality: 8},

}.each do |day, attrs|

context "when it is day #{day}" do

before { day.times { gilded_rose.update_quality } }

it { is_expected.to have_attributes(**attrs) }

end

end

Or, using RSpec’s shared_examples feature:

shared_examples "change by day" do |day, **attrs|

context "when it is day #{day}" do

before { day.times { gilded_rose.update_quality } }

it { is_expected.to have_attributes(**attrs) }

end

end

it_behaves_like 'change by day', 1, sell_in: 9, quality: 19

it_behaves_like 'change by day', 10, sell_in: 0, quality: 10

# ...

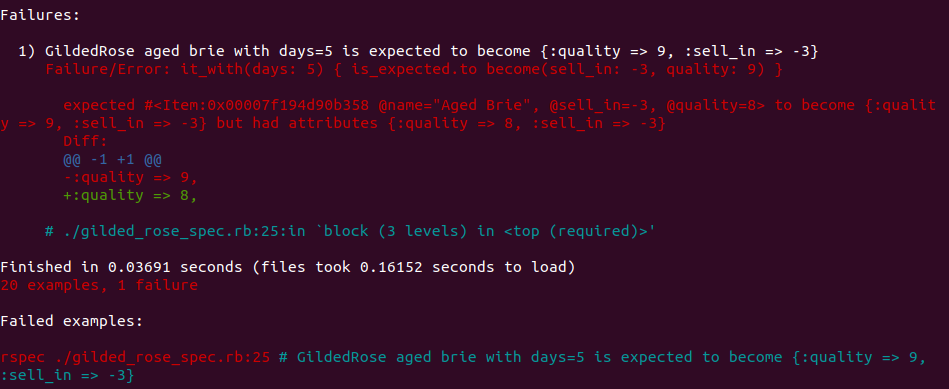

Both of these options have their merits, but I preferred it_with approach here because it doesn’t have any indirections (like, a pair of input/output in one place, and how they are related is in the other), so when something fails, it shows exactly the line that failed. If I deliberately break one of the tests, RSpec will clearly point to the line it is broken (I am deliberately changing one of the tests to be failing to showcase this):

And the last line is exactly the command you need to restart only the failing test for quick debugging (which is harder with truth tables/shared examples).

Note also pretty informative test and error description produced without any additional text written by the developer. It is not very grammatical, but pretty clear.

The implementation

With tests properly passing, now to implementation.

When rereading the requirements, we might notice that all conditions can be described as a simple dependency (name, sell_in) => change of quality.

The most natural representation of this in the modern Ruby would be pattern matching. So, quite quickly (with a few failing tests and numbers tinkering), I’ve come up with this:

class GildedRose

def initialize(items)

@items = items

end

def update_quality

@items.each { update_item(_1) }

end

def update_item(item)

return if item.name == "Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros"

change =

case [item.name, item.sell_in]

in ["Aged Brie", ..0]

+2

in ["Aged Brie", _]

+1

in ["Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert", ..0]

-item.quality

in ["Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert", ..5]

+3

in ["Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert", ..10]

+2

in ["Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert", _]

+1

in [_, ..0]

-2

in [_, _]

-1

end

item.sell_in -= 1

item.quality = (item.quality + change).clamp(0..50)

end

end

There aren’t many moving parts here:

- quick guard clause for “legendary item” that basically doesn’t require any processing;

- almost literal rewriting of requirements into simple correspondences “with this name & range of values of how many days left: that change in quality”

- the requirement “quality never goes below 0 and above 50” straightforwardly translates into Comparable#clamp; this allows decoupling of change of the value from the range control (instead of the naive initial “if it is inside limits, do the operation”).

For further clarity, let’s walk through a part of it, with comments (shortened the name of the item so the code will take less place horizontally):

case [item.name, item.sell_in] # we match pair of (name, days to sell)

# ...

in ["Backstage passes", ..0 ] # if it matches (backstage pass, anything <=0)

-item.quality # remove the rest of the quality

in ["Backstage passes", ..5 ] # otherwise, (backstage pass, anything <= 5)

+3 # +3 points: I used (optional) + to underline the meaning

in ["Backstage passes", ..10] # ...and so on...

+2 #

in ["Backstage passes", _] # if name still matches, and ANY other days to sell

+1 # the fallback value

Note that inside pattern matching, Ruby uses #=== matching method for every value in an array, and beginless range (..0: range from -infinity to 0, including it) has its === defined so that it returns true for a number inside the range.

That’s, kinda, it! The core method is 25 lines now (including blank ones); at the same time, it is only four simple expressions and only one level of condition/nesting.

Random fun fact: Ruby linter/style checker Rubocop with default settings would complain that:

- Cyclomatic complexity for update_item is too high. (10/7)

- Method has too many lines. (22/10)

- Perceived complexity for update_item is too high. (10/8)

Judge yourself whether the complexity and length of the code in front of your eyes is that criminal! (In my opinion, our obsession with “small simple methods with very descriptive names” went too far many years ago.)

One more notice: the original kata’s text suggests “not to re-write the code from scratch, but rather to practice taking small steps, running the tests often, and incrementally improving the design.” What I did, though, demonstrates one of the things I’ve learned to trust through my career: when meeting with really problematic code, it is frequently easier to rewrite [parts of] it from scratch, at least on a small scale. Iterative improvements might never converge to something that clearly says what the original intention was!

If I hadn’t been provided with the requirements when meeting the code like that, I’d probably move for some time with iterating improvements till the original requirements would become clear—first and foremost, trying to make if linear (even at the price of repeating conditions) to see how many branches are there really; and then considered whether there is a better way to implement those requirements. (I tried to demonstrate that in a series of commits to a separate branch, but early on in the attempt, I understood I was not doing an honest job. I couldn’t shake away the knowledge about the requirements, so I was too quickly shortcutting to “oh, anyway, I know why this < 50 repeats in many branches”. If I stumbled upon the kata again, it would be fun to try to honestly restore the requirements from the code without reading them first. But it is what it is.)

What it would take to implement a new requirement

Let’s remember that the whole kata’s goal was to make updating the code easier. So, back to that newly emerged requirement:

We have recently signed a supplier of conjured items. This requires an update to our system:

- “Conjured” items degrade in

Qualitytwice as fast as normal items

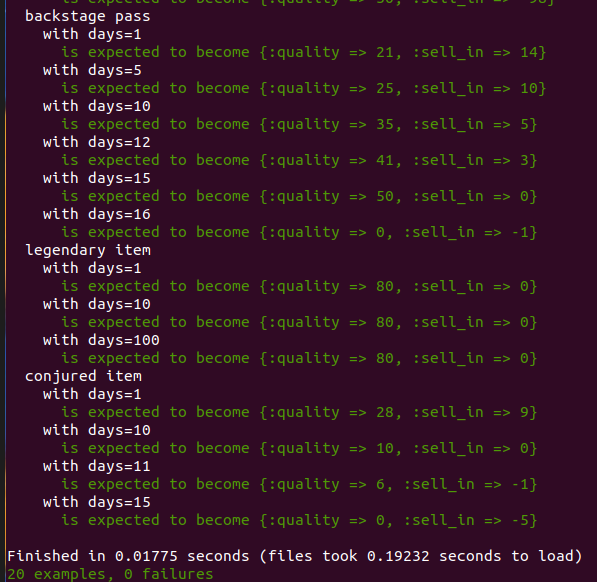

Specifying that will require adding this tests block:

describe 'conjured item' do

subject(:item) { Item.new(name="Conjured Mana Cake", sell_in=10, quality=30) }

it_with(days: 1) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 9, quality: 28) }

it_with(days: 10) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: 0, quality: 10) }

it_with(days: 11) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: -1, quality: 6) }

it_with(days: 15) { is_expected.to become(sell_in: -5, quality: 0) }

end

…and this to the main case of the implementation:

in [/Conjured/, ..0]

-4

in [/Conjured/, _]

-2

(As explained above, pattern matching uses === to check individual values, and Regexp#=== can be utilized here to handle “any string that starts with”. Random fun fact: many nice refactorings suddenly break on the necessity to handle string inclusion instead of constant strings to identify the necessary case.)

So, an eight-line change in total, including blank lines (the commit is somewhat bigger as it also updates the integrational test).

Well, seems not that bad, actually…

A postcard from 🇺🇦

Please stop here for a moment. This is your regular mid-text reminder that I am a living person from Ukraine, with the Russian invasion still ongoing. Please read it.

One news item. Photos emerged on social media showing russians executed an unarmed captive Ukrainian soldier with a sword.

One piece of context. Many international festivals decided to screen the “Russians at War” movie by “Canadian” director Anastasia Trofimova. It is claimed to be a documentary, but it is actually a propaganda piece by a person employed by RT Russian propaganda channel.

One fundraiser. The PayPal fundraiser for the most critical Pokrovsk frontline direction.

Is that really it?..

So, an honest question one might have: if it was real application code, would I really leave it like that, in one method with many conditions?

With this amount and uncertainty of requirements, honestly: yes!

One thing I am not happy about here, though, is the repetition of the name check in the pattern-matching solution. The possible alternative, which is kinda “DRYer”, is using ole good case/when instead:

change =

case item.name

when "Aged Brie"

case item.sell_in

when ..0 then +2

else +1

end

when "Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert"

case item.sell_in

when ..0 then -item.quality

when ..5 then +3

when ..10 then +2

else +1

end

else

case item.sell_in

when ..0 then -2

else -1

end

end

The solution has its pros and cons:

- pro: no duplication on name check; more visible logical blocks per item group;

- con: duplication of the condition

case item.sell_in—which is somewhat harder to notice (that all the checks are by the same parameter) and somewhat easier to break (i.e., introduce another part of the logic that makes the decision by another variable and start losing the whole picture).

In real application, I might’ve chosen one of the two (or switch between them during development), depending on what feels better at the moment!

With the growth of the cases number (or if I’d felt extra-architector-y), I might’ve also considered a data-based approach: construct a constant hash of conditions like…

{

"Aged Brie" => {

..0 => +2,

1.. => +1

},

"Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert" => {

..0 => :nullify, # a special value "drop it to zero"

1..5 => +3,

6..10 => +2,

11.. => +1

}

# ...and so on

}

…and then a code that chooses the change based on that.

But only after understanding I have enough cases to decide what is the exhaustive structure for such a constant (and if we really have one).

Which leads us to the following question…

But what about asbstrakshunz?

Apparently, the first intuitive reaction of many Rubyists (and not only them) to a task like that is thinking about representing each of the cases as a class that implements the corresponding piece of logic. It is so widespread that I have a term for it: knee-jerk OOP.

I was like that, too. But with years, I learned to keep my OOP reflexes at bay—as well as any early “let’s abstract it!” urge (like the aforementioned “constant extraction” idea).

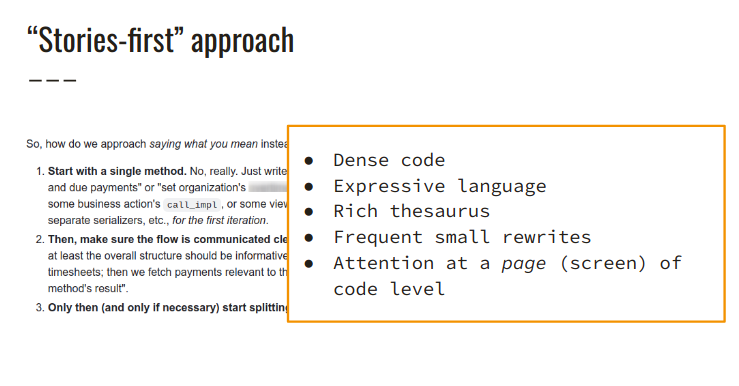

While the amount of code implementing some algorithm is no more than one screen, roughly, it is frequently beneficial to keep it all together to see the whole story at once. This way, when we don’t need to navigate through many classes/small methods, we can clearly see what variables change non-trivially (only quality, with sell_in being absolutely trivial), and variants of behavior we have (constant increase, constant decrease, nullify), and it is immediately obvious that we don’t (yet?) have cases like “quality halves every day” or “it depends on the weather”.

I call it the “stories-first approach” (a slide from my recent EuRuKo talk, I hope the video will be published soon):

Once there is more code (as the amount of conditions in the kata requirements is, of course, toy-ish), we might begin to see the appropriate structure for it, which might be quite different from the knee-jerk one! Would there be more “legendary” items, and would this mean the same thing every time (“just a constant quality and no sell_in change”) or a new thing every time? What types of quality changes might be there, other than “increase/decrease/nullify”? Which types of the “change by” value changes are common, and which are accidental?

Only having more than one screen of possible cases might we need to try finding things to extract. And quite frequently, the things extracted might happen to be small utilities, new “words” in the language the “story” is written in, instead of splitting one story into many independent ones!

That’s it for now. Hope it was an interesting journey into another person’s thinking process, even if you disagree with some (or all) of the conclusions.

Thank you for reading. Please support Ukraine with your donations and lobbying for military and humanitarian help. Here, you’ll find a comprehensive information source and many links to state and private funds accepting donations.

If you don’t have time to process it all, donating to Come Back Alive foundation is always a good choice.