Notes on code, text, and war. Week 1: Believing in text

Writing texts is the most useful and fruitful metaphor for software development.

After 25+ years of writing software and at least as much of writing texts, this is the one thing that I have become sure about.

This also means that reading, writing, editing, and layouting concrete chunks of code is a central activity of software development. Not planning, not scheming, not calculating and measuring. All of those take their place—like in writing complex texts, they do—but the most direct and useful experience we can have is still that of getting our hands on the code.

Does this point of view stand in the age of LLMs? I believe that not only it does, but becomes stronger and more productive. The LLM breakthrough (however many ethical and ideological concerns we have about it; I have plenty) is a direct consequence of the vast number of texts written by human civilization. It is also a direct cause of the explosive increase of this number. Whether you intend to resist it, utilize it, denounce it, or ride it, looking at everything as text is a useful tool of though.

Depending on your experience, work environment and cultural background, the focus on code-as-text might seem painfully trivial. Or it might seem screamingly irrelevant and wrong. But bear with me for some time. I think that I am able to show many practical implications of focusing on this. Some non-obvious implications, too.

For this, I want to write a series of (relatively) short posts/notes: after a long silence in my blog, I have things to say. Things that might provide others with some new perspectives/ideas. Or, at least, irritate in an entertaining way!

Previously, my writing was mostly focused on Ruby. (Save for a few long digressions to “open data” direction—the direction that was almost entirely cannibalized by global LLMs now. So what, fewer things to think about.) I am still quite fond of the language; I still use it daily. But what I like to think about now is much less Ruby-centric, though in many aspects inspired by my experience of writing in it for many years, and even participating in the language development.

“Experience” is an important word for me. And frequently definitive for the topic I chose.

We write and read to share the experience. Not in a narrow professional sense, but in a broader cultural one: My text allows you to experience what I lived and you didn’t, and vice versa.

Prose shares the experience of stories. Poetry shares subtler experiences of feeling, inspiration, and insight.

Utilitarian texts—like journalistic, academic, or “texts” in programming languages—share the experience of understanding something. Not the knowledge/understanding itself, but the experience of understanding from a particular person. Alongside the experience of being this person, with their education, habits, expertise, and personality.

Say, here is my experience: I am a lifelong software developer, primarily writing in Ruby (since at least 2004), and for some time, I actively participated in language development and documentation. But also, I am an author of prose and poetry, with some magazine publications, festivals, and a relatively popular novel published just last year. But also, I am Ukrainian, living through war, serving in the Armed Forces, with some combat experience and current duties not completely unlike my civilian ones (though nothing more precise can be said of them).

Obviously, I compartmentalize my experiences to some extent. Sometimes to the extent of switching to almost unrelated personas. But for a deeper look, this is an illusion. Obviously, each “persona” draws from the experience of the other. I plan novels not unlike the way I plan software projects. I care for expressive code and constantly think about how others achieve that (and how they fail), not unlike in my literary work.

And, as a person living through a genocidal invasion of the former empire, and knowing what led to it, and observing how the world responds to it, well… I think I became more attentive to the weight of proper representation of information, to cognitive biases codified in texts (and software), to consequences of exaggerations and omissions, overstatements and understatements. Even in the most routine work during software development.

In my 2024 EuRuKo talk “Seven things I know after many years of development” (video; transcript article), I tried to blend my war/programming experiences. People say it was insightful for them. Maybe they are just being polite.

Anyway, during the work on the talk, I came to the emphasis on truth and clarity as the primary goal of code writing. Even the most mundane code writing.

Not directly related to the text above, but related to the living experience of Ukrainians, here is a truth.

Almost exactly two years ago, on June 6, 2023, Russians blew up the Kakhovka Dam on Ukraine’s main river Dnipro, draining the huge Kakhovka reservoir and flooding some 600+ square kilometers of populated land and natural reserves.

Even the approximate number of victims is still unknown: on the left bank of the river, still occupied by Russians, there were no efforts neither for immediate relief nor for subsequent recovery of bodies. The environmental, humanitarian, and economic damage of this man-made event is said to be comparable to a nuclear explosion.

There were many texts written since about the cause, consequences, and aftermath of the catastrophe. A major part of international ones—immediate news as well as subsequent assessments, political statements and philosophical essays alike—had a strong tendency to diminish the effect, or shift the blame towards “natural causes,” or “harsh realities of war.”

There were no strong consequences for Russia, other than the—usual and used-to—”public condemnation” (and even that expressed in no clear terms). There were no new sanctions other than those already planned, regularly slightly expanded, and regularly easily circumvented.

Even today, English Wikipedia prefers the passive voice of “the dam was breached” with a cautious explanation like “many experts say it was Russians, but Russians deny that, so in the interest of Neutral Point Of View that’s all that can be said.”

This is just one of the many examples that might explain why I am so obsessed with truth and clarity, and how what we write and what we read structures our understanding. In texts and code alike.

We’ll get back to the code at some point. But right now, I want to highlight one text written in the aftermath of the Kakhovka Dam explosion.

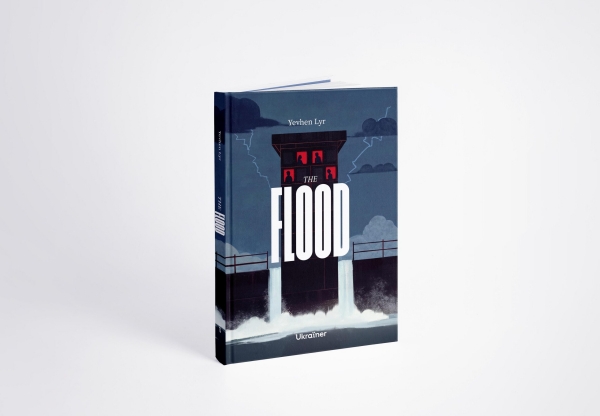

It is a book that was announced just a few days ago, on a sad anniversary. “The Flood“ is a narrative non-fiction, “a journey into the heart of the Khersonian steppes, a story of loss and resilience seen through the eyes of witnesses.” It is written in English by Yevhen Lyr—a brilliant Ukrainian writer, translator, educator, and volunteer who was there in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, one of those dealing with its consequences.

Now, he is a soldier.

Many of us are.

Sometimes, I still have people in comments and Internet discussions of my technical articles wondering how we can live like that. Meaning, how tragedies of the scale of Kakhovka Dam, or nightly shelling of cities, or constant deaths of people we know, might coexist with what looks like “normal life”: like this blog, or new Ukrainian books, or concerts, or parks, or new cafes. How do people move forward with their lives? (Sometimes those questions are compassionate, and sometimes they are sarcastic or reek of suspicion: this so-called “war” shouldn’t be that bad if you write about programming or visit a concert?)

Here is one more truth for you: you get used to anything, given enough time.

A human being can only stay in shock for so long. And “so long” here is hours and days, not months and years. Then (given at least some pockets of pretend normalcy), you get back to who you were before. Not completely, but to some visible extent.

Almost every day, we have awful “anniversaries” like Kakhovka Dam ones: death, destruction, occupation, loss. From the past three years of the full-scale invasion. From the previous eight years of hybrid war. From hundreds of years of colonial attempts to erase our identity.

And it is not just anniversaries of past events, of course. It continues and becomes worse.

Last weekend, my home city, Kharkiv, where my family still lives, survived the largest combined aerial attack—kamikaze drones + various types of rockets + gliding bombs—since the beginning of war. Just last night, our capital Kyiv survived another one.

And so on. And so on.

Oh wait. I wrote the previous paragraph yesterday but didn’t finish the article just then. This night, Kharkiv was again attacked by 17 large kamikaze drones at once, targeting populated areas. At least sixty people are injured, at least two dead.

And: we still live here. Soldiers and civilians, grown-ups and children alike. “Our cities are too inconvenient for Western media” is one of my short texts that I wrote over the last three years. There are several more.

Trying to write those texts—trying to explain anything, anything at all—sometimes also feels absurd. And sometimes as just a way to distract myself. But I am still writing. Less of “explanations of our life for foreigners” (who aren’t that interested anyway), more of code, and my literary work, and my poetry translations, and now, hopefully: this series of cross-topic texts.

What does it all have to do with the “code as text” concept? Maybe nothing. Maybe everything.

The humane part of the software development craft always appealed to me more than anything else. But this part exposes itself only over time. Let’s put it this way: a reasonably dedicated developer can implement any reasonable idea in any first way they think of. Like, you can convey urgent news or a fresh thought in the roughest, most incoherent words, and still pass the information.

But for an idea to live, for a project to evolve, to preserve velocity and maintainability, you need something more. Some ways for all of it to continue make sense. I say it in the most pragmatic way: a growing and ever-changing system like a software project needs a way to maintain coherence and not fall apart. Even developing the most pedestrian features and performing the most mundane refactorings, I never stop thinking about the ways we convey messages and preserve truth. I continue to learn. I continue to try to share my experience.

I don’t know if what I am saying makes sense right now.

But I’ll be trying it to, with more pragmatic, hopefully regular, chapters, roughly related to the “code as text” topic. And to war.

See you next time.

Thank you for reading. Please support Ukraine with your donations and lobbying for military and humanitarian help. Here, you’ll find a comprehensive information source and many links to state and private funds accepting donations.

If you don’t have time to process it all, donating to the Come Back Alive foundation is always a good choice.