Why Wikipedia matters, and how to make sense of it (programmatically)

Some time ago, I wrote a Twitter thread about one of the unseen hard problems in software development—access to the common knowledge.

Since then, a few things happened to me, one of the most important being the inception of the new project trying to attack those problems, named WikipediaQL (that had already attracted some positive attention even in the early stages it is). I am still working on that project and plan a series of articles on the problems of common sense knowledge extraction and practical approaches to it.

As a prelude for this series and linkable justification of various aspects of my work, the current article is the (more orderly) republishing of the Twitter thread above.

Here goes.

The problem

Some of the hardest problems to bring in the software development ecosystem are those that “intuitively” have an easy answer. (They are hard because before starting to discuss possible solutions, you need to persuade people it is something non-trivial and worth thinking of. And after they understand, they become sad and don’t want to think about it either. I saw it discussing the spellcheckers.)

My favorite one is about common sense knowledge.

Anyways, about the common-sense data/knowledge. How many people live in Albania? What’s the title of Game of Thrones S05E07? What books had Tove Jansson written? When was Google incepted?

How’d one answer those today?

Yeah, I know! You google it (or you duckduckgo it), you look into Wikipedia, you ask Siri. But how’d you answered these questions if you are a developer and need to use the data in your code? And here the “hard problem that seems easy” starts.

While discussing this matter, I am frequently asked, “but why do you need to answer those questions in code?” But for me, this is not a question. For me, it seems self-evident that all the “commonly known facts” should be available in the computable form, THEN we’ll see why. However, in our age of ubiquitous computing, the necessity of augmenting our understanding of the world around us with ever-present common knowledge seems to become obvious.

How we do it

So, what’s our (developers’) typical way of using common knowledge in the code? “Just find a good dataset or API, there are plenty”, right?

If only!

“Just find dataset/API” (or copy it from encyclopedia if the data is short and static) approach has too many limitations. You need a good and reliable source, which is timely updated (even country names change!), provides all the data you need, and, ideally, is free.

But once you find it for one problem (list of country populations) and switch to another one, similar (city populations), related (country’s elevations) or unrelated (Game of Thrones), you need to start over: find a source, handle it’s API/format/validate it…

…and let’s not forget that for more “interesting” datasets, you’ll hardly find a free and open data source, if any. Good luck with looking for TV series episodes list API, which is free, relevant, and unlimited in use! (“Why should it be available”—one might ask? But intuitively, it is public, open, and readily available data. You don’t need to pay anybody or hack anything to remember when the last Doctor Who season was aired.)

How they do it

So, closer to the point. Can we do better? Many years ago, I was fascinated (still is!) with one of Stephen Wolfram’s articles/demos (before that, I’ve used Mathematica a bit in uni but thought about it as a very smart calculator). This one, probably.

There is a lot of cool stuff in Wolfram Language, and cool in a special way, so you immediately start wondering “why other languages/environments don’t do that” (at least I do). For me (again!), the coolest was the “integrated data” feature of the language.

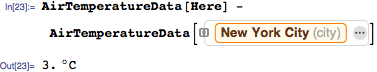

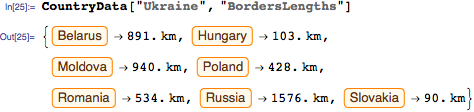

Here are some examples (just copy-pasted from the link above). The revelating power of those was incredible. “But effing why can’t all of us has this???”

Note that all of the reach reality-describing values can be operated upon just as regular data types, put into variables, sent to methods, etc.

However awesome Wolfram is, it is a proprietary technology with proprietary data. I am a firm believer in open source and open data; and it seems especially suitable belief when we are talking about common knowledge.

BTW—and this is an important side note—it seems that many behemoth IT corporations build and maintain their own “common knowledge datasets.” And I have no warm feelings about this because it gets worse.

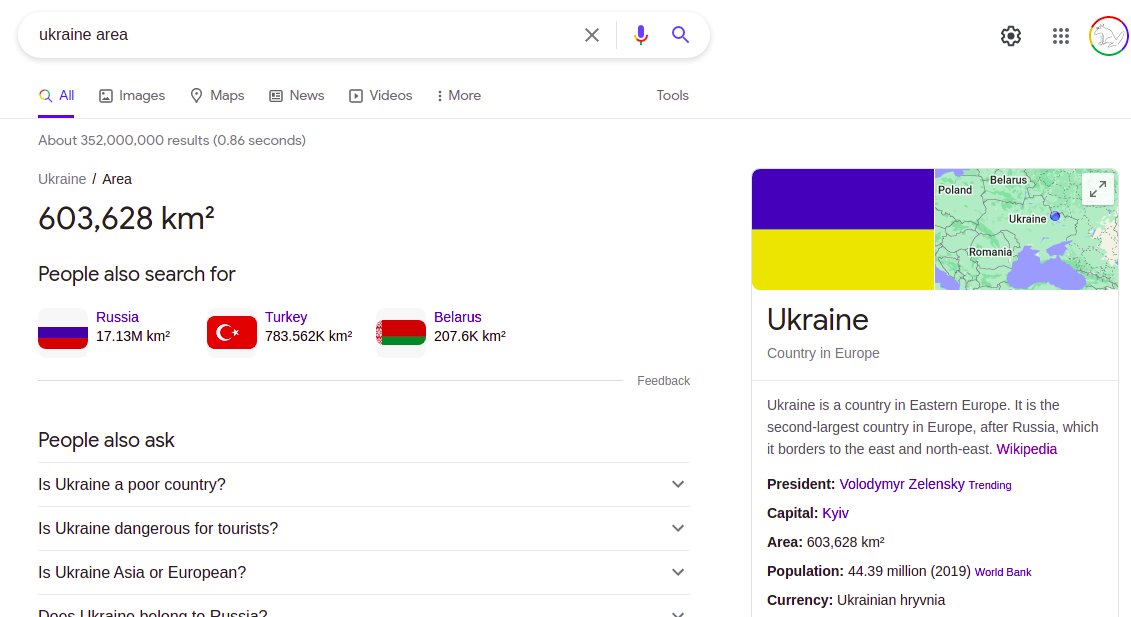

Some time ago, they just helpfully provided Wikipedia as the first result for common queries (like “%country name% area”). Then, even more helpfully, they started to extract and show the data inplace under the Wikipedia or other data source link.

Then, they started to show just a card with info, no data source. “Who says so?” Google does! Because Google knows! (notice the card at right has links to sources for some of the info, but it is just small links. For some of the info).

So, the data is theirs now. And, of course, you can’t have a nice API to use it programmatically!

And here is the centerpoint of this article: I really do believe one should be able to write (in Python, Ruby, Haskell, whatever) something to the meaning of World.country("Ukraine").attr("area") and receive a meaningful answer. For any/most of the “commonly known”.

I do believe that it “just should be possible” and would bring the power to investigate, play, experiment, check, observe and invent.

But how?..

So, back in 2015, I started to think about “How.” I was young(er) and even more arrogant than today.

Huge spoiler alert for the rest of the article: I still didn’t build something very cool or useful in the process of investigating the topic. But I gathered a fair share of insights. And became older (but that’s probably unrelated).

The first question to ask: Do we have enough open data about common facts AT ALL, or maybe it is only possible for a huge corporation to gather?

Obviously, we do. It is called Wikipedia. (And OpenStreetMap, and several others, but Wikipedia is The Table of Contents.)

The problem with Wikipedia (in the context of this topic, anyway) is that Wikipedia is for humans. And by humans. It tries to be almost regular (= parseable) in some cases but manages to persist irritating small irregularities everywhere.

There are attempts to build a machine-parseable counterpart of Wikipedia, most notoriously Wikimedia’s own Wikidata. Unfortunately, Wikidata still covers a fraction of the knowledge.

You know what? I had a dedicated thread on it:

1/N. I recently mentioned @wikidata in a discussion with some colleagues, and once again understood people frequently either unaware of its existence or consider it as a "side-project" (merely curious, mostly for data geeks). Which is somewhat understandable but oh so wrong

— zverok (@zverok) April 1, 2021

So, I do believe that today Wikipedia is our best guess for machine-readable data. And following this belief, I made several experimental attempts a few years ago (not ignoring Wikidata, either).

The doomed (yet fun) attempts to solve it all

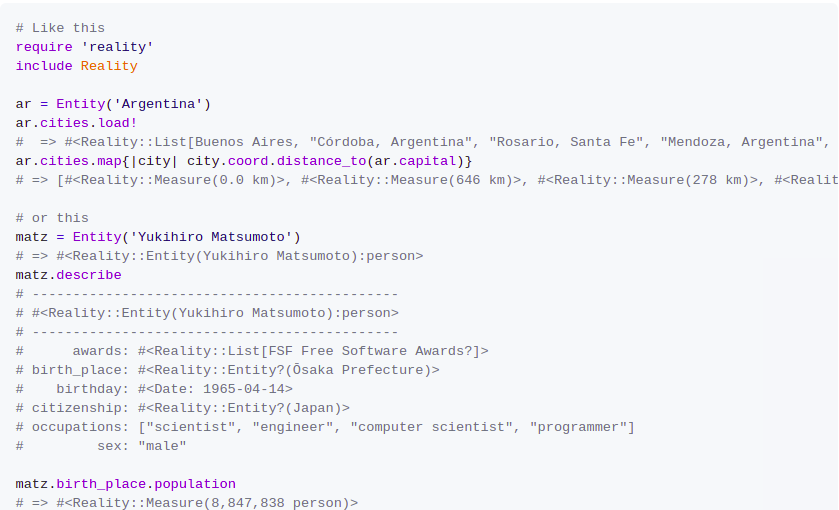

Below is a classic pair of “How it started / How it’s going” screenshots of the Reality project (or “Molybdenum/Reality”, because I was unable to abstain from punning on Wolfram).

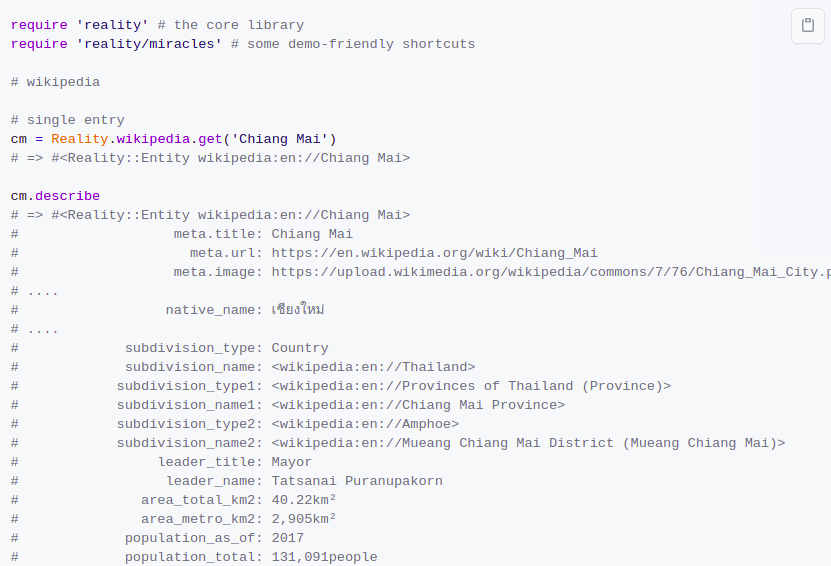

1. The first working prototype. At first, I was looking for “coolness” (it is nice to imagine you can represent every property of the real-world object by a method).

2. The latest prototype I still developed and demonstrated. By this point, I started to strive for completeness and consistency, looking for a data/coding model that would be truly extensible.

The video and slides of presenting the latest version at RubyConf India.

Honestly, it was fun while it lasted.

Honestly, I made all possible errors on this project. First of them was—to my great sorrow—doing it in Ruby. (See “I was younger.” I believed that it could be as hype-generating as Rails was and draw people back to my beloved language.)

I still think Ruby is really good for implementing and using such kind of an experiment—but that’s not a surprise considering my love letter to the language. But it should not have been done in Ruby. I should’ve gone to where data communities are.

And I should’ve thought, first of all, about the principle of data access approaches, not about a cool library for some language (even the best one!) It brought me my share of the conference fun, but that was that.

The repo link, if anybody is interested (but this post is about the principle, not about sad, cool, small abandoned pet-project).

Another funny thing I’ve discovered: I believed that parsing Wikipedia markup is the best way of extracting structured data (and developed my own industrial-strength parser because of course I did.) Only years after, I understood that rendered HTML is much more regular. I could’ve saved myself a few months!

And of course, I’ve discovered a lot about the complications of modeling real-world objects with programming language “objects.”

The only time HackerNews mentioned the project was somebody making fun of an early prototype because

Entity('Spain').continentreturned'Africa'(Who could guess some countries are on several continents when you want nice and cool.continentmethod, right?..)

Now what?

But even all those years after abandoning the project with the coolest name ever (and I didn’t even get to implement the Reality.check! method, would you believe?), I still think that we need to unlock these gates.

We need to parse our civilization’s knowledge and make it programmatically available to everybody. And then we’ll see what’s next.

This year, I am starting to attack a problem from scratch: now with Python, and from a different angle, with the WikipediaQL project.

Follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list to see the road together.