What you can learn by merely writing a programming language changelog

Adventures in understanding, explaining, and challenging the facts that should be obvious. (Part 1 → Part 2 → Part 3)

This article is written for my Substack, you can subscribe to it by email now!

First of all: I am deeply fond of Ruby-the-language. I have strong and frequently harsh (probably harsher than yours!) opinions on Ruby-the-tool in its current prevalent usage and some frameworks and practices associated with it. But the language—after 17 years of everyday use—is still incredibly helpful for my thought process, and I only half-jokingly call it my mother tongue. At least when thinking of the problems that could be formalized.

So, I understand the text below might be read as bragging. It can also be read as a critique of Ruby’s development process or even witnessing its inadequacy. I assure you, it is not the latter. Am I bragging? A little: I do take pride in my work. Am I describing the broken language development process? I believe not. I describe a process that is different from some other languages and some industry expectations—but at the same time, I concede that it is the only development process suiting this language.

Second of all: I am not asking you of the same fondness to Ruby or any at all. I believe the story I will tell can be interesting even for non-Rubyists, those who have never written in the language, and those who resent or despise it. It is a story of what happens when you “just” try to understand and document the reasons and consequences of new features of your programming language—once per year, every year. This story is full of surprises, heated discussions, moments of enlightenment, and moments of despair. It is also a story of caring and being involved.

It goes like this.

December 2018: How it all started, or, Good things could come from negative emotions

Vampire: Like my daddy said right before he killed my mom, “If ya want somethin’ done right, ya gotta do it yourself.” — Blade 2

I have been writing in Ruby since 2004. Unlike many others, I’ve come not because o Rails (and managed to mostly avoid Rails till 2016, I think), but due to the language itself. I always felt it fitting extremely well to my mental models of programming, and always expanding them.

My understanding of how the language should evolve also expanded with time. By 2018 and the wake of Ruby 2.6, I became very active in Ruby Issue Tracker, which is almost the only thing where the development happens (more on this below). A few language features I proposed and defended made it into the release. A few other things in the release made me happy, too.

Ruby is traditionally released every Christmas. A few weeks before and after that date, many blog posts occurred listing and explaining new features—and that year, I became very attentive to them. And quickly discovered I was not happy with either.

Some were written by language enthusiasts explaining a few features they care about. Others—by consultancies and studios trying to keep their marketing blog alive, just retelling the (dry) official NEWS-file in their own words. Neither was wide and deep enough to make people feel why new features are designed and what their consequences are.

So, after a few /r/ruby ramblings about this (which I am not proud of!), I decided I’d rather do the “right” list of changes—aka “changelog”—myself. And I did it, and doing it since then. And it turned out a much harder job than I imagined—but also, much more consequential, too.

Should be a simple thing to do (or, the rest of the effing owl)

When I started to do The Proper Changelog a few days before Christmas 2018, I had a pretty clear vision of what should be there. This vision turned out to be valid. I also had some clear estimation of how much time this should take—one or two spare evenings—now, the estimation turned out to be total BS.

It took closer to two weeks of very intense work and a few sudden discoveries on the road.

The experience was quite humbling, not to say humiliating at moments. And not because I’ve underestimated the task—as a professional developer, I am no stranger to too optimistic estimates—but because I needed to learn a lot.

After almost fifteen years of loving and using Ruby and several years of following its development, I was (vainly) smug about me knowing everything I needed to fill the changelog even before I started. But—

First and obviously, each feature needed a link to official docs. It seemed the simplest thing to do (grumpily: and still missed by most “what’s new” blogs), but I discovered, to some surprise, not all of the changes were reflected in documentation updates.

It was my first deep glance into the peculiarities of Ruby’s development process—but by far not the last. It felt like updating docs when the code is updated is the responsibility of those who commit new features, and commiters don’t always have enough time and resources to do that.

So, one of the side effects of the changelog creation was me providing patches for the documentation missing.

Next, I wanted to describe the reason for every not-immediately-obvious-change. Again, it started egotistically: I wrote a “Reason:” point for the three changes I argued for and considered important. Simple fairness now required me to explain the other ones with the same thoroughness—even for changes I didn’t care much about.

Now I needed to learn what others considered important about the language, investigate why they felt something natural, and how several opinions of “what’s natural” clashed in heated arguments.

I read through discussions observing how feature request mutates from the initial idea through several rounds of choosing the names (hard!) and protocols—and to the final approval (or alternative proposal) by Yukihiro Matsumoto, aka Matz, the language creator and ultimate final authority of the design.

Then, I provided code examples for most of the features, not only the most trivial usage. Sometimes, I felt it needs realistic examples of how it could be useful, thus complementing the “Reason”; other times, non-obvious behaviors needed to be demonstrated.

This stage required me to know myself, or, rather my unspoken expectations and intuitions about how Ruby usually behaves and how language elements are expected to be combined. Only then I could question and demonstrate how new features follow those intuitions and expectations—or break them.

In some cases, though, I became sure that the feature design does not follow those intuitions/expectations of an ordinary Rubyist (me) and raised concern in the issue tracker. In one case, I was persuaded otherwise; two others are still (after three years) under discussion.

The culprit here was, of course, raising the concern after the language version was released. At this point, “can we change this?” is the question for the next version (next year!) already—and sometimes is asked too late due to the backward compatibility (like the “timezones” issue above).

Though the fact that my concerns weren’t immediately dismissed taught me that questioning the design might be fruitful (spoilers: and in the next years, it frequently was!). It also made me curious about the whole Ruby language development process. The language always felt somewhat home-made to me: great overall care, but occasional uneven cuts or rough edges, now I started to understand why.

The end result (is that so?)

After those weeks of work, on Dec 29, 2018, I finally published the very first installment of the project I named Ruby Changes.

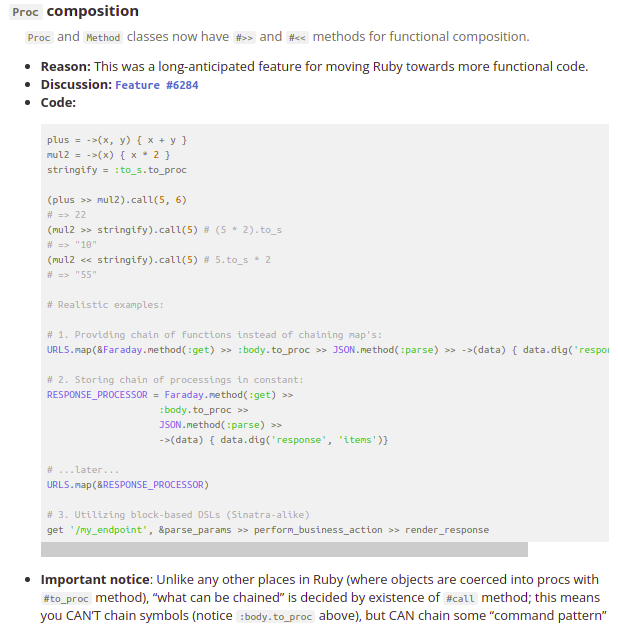

Example of one feature description

It turned out to be quite useful—and quite popular too (one of my rare endeavors that received the amount of attention it deserved according to my overblown expectations). It was retweeted by Matz himself, published in Ruby News Weekly, heavily upvoted on Reddit, etc., etc.

For me, it was a moment to exhale and relax… And make a mental notice to maybe next year start earlier!

But at the same time, it was the beginning of some larger story. Since that Dec 2018 rush, I started to follow Ruby development even closer than before and participate with more resolve.

Through these years, I reflected on Ruby’s development process, which is quite different from other languages I follow (say, Python and Rust). In the second part of this text (in a week, hopefully!), I’ll try to catch the essence of what is uncovered for me and how it made me sometimes critical, sometimes supportive for the group of Ruby developers—which turned out to be smaller and more open than I expected.

I am writing this mere two hours after publishing this year’s installment: Ruby 3.1 changelog. I am still on board, and the way the language evolves and changes still amazes and amuses me to not a small extent. I’ll try to share these feelings next time.