Following the programming language evolution, and taking it personally

Further adventures in understanding, explaining, and challenging the facts that should be obvious.

(Part 1 → Part 2 → Part 3)

There are characters in me who do not talk to each other who fill each other with grief who have never dined at the same table

[…] but I with all of my characters go on caring for you

— Garous Abdolmalekian, as heard on The Slowdown, ep. 395

I deeply believe in language’s evolution that is unstoppable, inevitable, and perpetual. Be it the human language or programming language—all the same.

However, this is not a universally accepted truth in many programming language communities. Especially for mature, widely-used languages like Java, Python, Ruby, and especially when the language is considered good by its users (unlike old PHP or old JS), many syntax/API changes are frowned upon. Improving the implementation? Yes, everybody wants it faster, more stable, support more platforms; also, concurrency. But changing the language? What for? The language was already good three (four, five) versions ago; every new syntax is just an unnecessary syntactic sugar!

That’s not how I see it. With years, I understood my main motive for writing the changelogs for Ruby: to put changes in the context, to try explaining how they logically follow from existing language intuitions, and how they invoke the urge for the next changes.

Working on changelogs, though, brought a lot to discover and understand about Ruby’s development process. And now I am telling this story.

This article is written for my Substack, you can subscribe to it by email now!

Never look back you should

The one where changelogs for older Ruby 2.4 and 2.5 are created, and some things become clearer about the Ruby development process (spring-summer 2019).

After my experiences with Ruby 2.6 changelog, I somehow got the idea it would be interesting to do the same for the last version of the language before 2.5; then, the version before it. I really don’t remember how this idea got born.

Ruby community, mostly, is just 1-2 versions behind the trunk (and it is encouraged by previous versions becoming EOL soon). However, from looking at others’ code and discussions, I noticed many people are still not aware of newer-but-not-that-new language features. Maybe I wanted to improve this situation, to provide contexts and descriptions. Maybe I felt my own understanding of the language would be improved (it was!). Maybe, I wanted to catch insights on the development process and to see whether it is always as rough at the edges as during 2.6.

Or maybe, as one old sci-fi author said, after all the work on parts of big systems, you just want to see something concrete done by your own hands—even if it is as inconsequential as a pile of clean plates. Or, a changelog for an old version of your programming language.

Anyway, while doing changelogs for 2.5 (released in 2017), and 2.4 (2016), there were many things to learn—again.

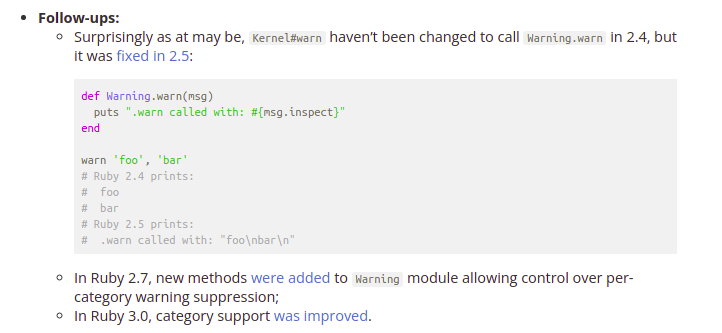

The quiet evolution of changes became obvious: when you have a perspective of several versions worth of changes at once, you can see how the mind of the language developers travels—the precious effect of “when introduced, this feature made us think of…”. I added a “Follow-up” item to some changelog features, exposing the effect.

Some features discovered in the older version were unfamiliar to me, despite their obvious usefulness. Yes, because they weren’t documented at the time of the introduction. (And yes, I fixed that.) The big picture started to reveal itself, the features and syntaxes playing together and their consequences being exposed. This vision made me bolder in proposing some more significant features—several I am still proud of got accepted in Ruby 2.7, which was in development that year. In one case, a questionable feature received a more sane alias in 2.5 and planned to be deprecated after that—but somehow, it wasn’t. You bet, I opened a ticket, and it was finally deprecated in 2.7 and removed in 3.0.

Looking back at the near history of your language turned out to be beneficial both for me and for the language. It also gives some insight into how the development process works—and in Ruby’s case, I corroborated the previous half-formed feeling of “homemade-ness.”

However unconventional, the process still produced high-quality core consistency but definitely lacked some housekeeping. Contributors came and went, some bringing much more improvement in a month than I did in the last four years. The core team worked hard on the, well, the core. But the whole process was—and still is—highly informal, and there was no single person, less the group, responsible for checking the docs, following up on old deprecations, and evaluating how small improvements looked together.

So, almost accidentally and reluctantly, I became this person. Or so I imagined.

All my puny sorrows

One where nothing goes as planned during the development of Ruby 2.7, and the author questions his commitment (Nov-Dec 2019)

The year 2019 was hard on me, in more than one way, but in the context of perception of my place in Ruby development too.

It started to look extremely promising for me: after publishing three changelogs (appreciated by the community), merging lots of documentation improvements, and participating/initiating the design of several new features, I felt being at the right place now. I wasn’t—and didn’t want to be—one of the decision-makers, but I felt—as always wanted—just a part of the evolution. I was bringing small additional angles to the shared perspective and was aligned with the core team enough for those angles to match their vision.

But then, a few unexpected things happened.

It was a big year for Ruby’s development. Next year—2020, “year of Tokyo Olympics” (little did we know!)—was designated for 3.0 release. And the 2019th version 2.7 was the last version before that, making it informally the last version to introduce some experimental ideas.

Taking offense for method references

One of those new ideas especially dear to me: method references. The thing is, in many languages like Python and JS, foo.bar() is the method/function call, and foo.bar is a reference to a method that can be stored in variables, sent to other methods, etc.

In Ruby, with its flexible syntax, foo.bar is already a call. There are good reasons for that, but it leaves the question “how do I get the reference to a method as a value” unanswered. For years, the best we could do was foo.method(:bar). It might even be considered logical, but not that convenient:

# read every file, usual way:

['README.md', 'Changelog.md', 'version.txt'].map { |name| File.read(name) }

# read every file, try to DRY it with a method:

['README.md', 'Changelog.md', 'version.txt'].map(&File.method(:read))

The second version is somewhat purer (no intermediate block to define, no local variable to name) but still wordy. For years, there were discussions about the method reference operator, which I personally was pushing for. Finally, before the 2.7 release, the .: form was chosen, making this possible:

['README.md', 'Changelog.md', 'version.txt'].map(&File.:read)

I was happy and started to write blog posts about it… But then, things got off the tracks—or that’s how it felt at that time. After lengthy discussions and iterations, another similar feature was merged—anonymous block arguments. This became possible too:

['README.md', 'Changelog.md', 'version.txt'].map { File.read(_1) }

It made me suspect that of two somewhat “competing” features in 2.7, allowing for shorter blocks, the anonymous block arguments will take more attention and overshadow method references—while the latter is much more important and consequential!

But it became worse quickly: the method references feature was reverted—and it was communicated in a way that made me feel offended! Like, one of the core team members didn’t like it, and everybody else was just indifferent… And that did it for the feature I considered the most important in the release! How’s that for “being aligned with the core team”?

Taking offense for pattern-matching

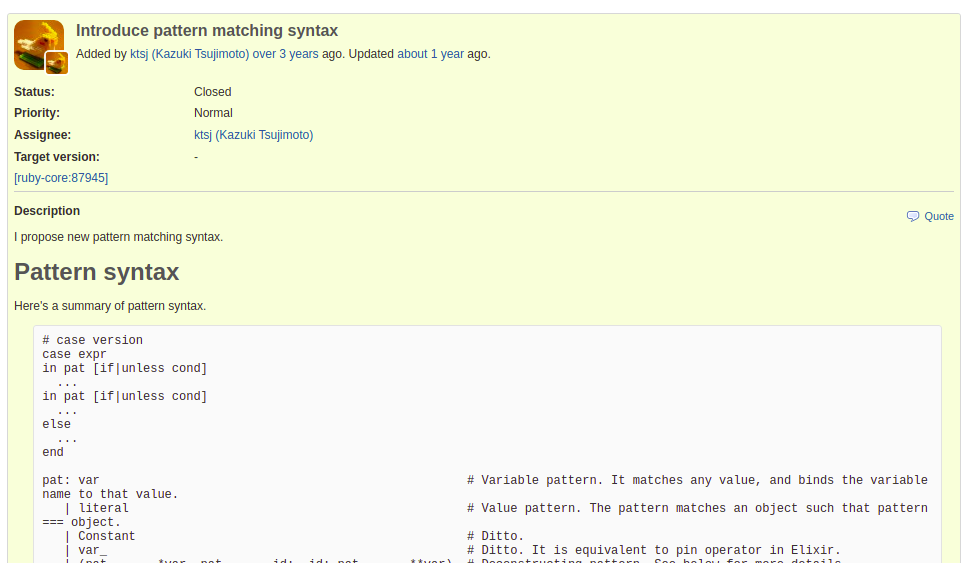

I was heartbroken, but it wasn’t even the last grief of the year. Another one—or what at the time felt like one—was pattern-matching merging.

I, as many of us, dreamed about “proper” pattern-matching in Ruby for a long time. In fact, my Ruby-dedicated blog was once started with an experiment in implementing it at a library level. I returned to the questions many times—as did others. As with method references, the potential syntaxes were discussed in the issue tracker, twitters, blogs, even conferences for many years.

And then, out of the blue—or so it felt—some pattern-matching syntax was just merged during Ruby 2.7 development. It seemed neat. It appeared even similar to my latest published ideas of how it should look¹.

¹I am happy to believe it was affected by my ideas… At least I know Matz has read/retweeted that article. But I can’t say it for sure: all in all, I didn’t try to invent something, I tried to guess what would be natural, so it might be just a coincidence.

But also, it was merged without any discussion with the community, didn’t seamlessly integrate with the rest of the language (pattern is not an object you can put into a variable/constant, for example). Oh, and it looked, again, as “one of the core developers invented it, and it was immediately merged.”

A lot of decision-making about Ruby is made in offline core team meetings—in Japan and in the Japanese language. And while the process became much more open in the latest years, non-Japanese Rubyists (me included) are sometimes too quick to infer that “they” are deciding everything without “us”.

So… Yeah, I became offended again.

Making peace and moving forward

What would you do? What would you feel? I felt like some great understanding I worked hard for was slipping away. That feeling of “solid core, maybe rough edges” started to dissolve: I doubted the core is solid anymore, with syntax elements this important decided on a whim.

Of course, I was wrong—twice wrong, one might say: both in my quick conclusion about the direction of the language lost and in having feelings this strong about it.

Some might say it is wrong to have any feelings about the software you develop or projects you participate in—but that’s what I do. Writing code is a big part of my life; I take pride in what I do, and I approach it with my “true self,” and most of the time, I am efficient due to this approach.

But of course, feeling offended by the decisions of others instead of trying to understand is never good for you. Thankfully, meditation helps. And an intention to always try to understand things helps, too. And that’s what I do—both in my professional and personal life.

It took me several months to adjust my mental image of how things are now in Ruby. And it will take me one more week to finish the story of how it happened. Next week’s part will describe my meeting with Matz at RubyConf Nashville, finishing of Ruby 2.7 changelog, struggle with documenting the new and shiny pattern-matching, and moving forward towards Ruby 3.0 and 3.1—which posed their own challenges.

I hope I keep you entertained with this weird over-sharing kind of development write-ups. And I’ll be happy for any feedback.